WERBUNG nicht mehr, nicht Werbung, [1] entwachsene Stimme, [2]

Wooing no more, not wooing, shall, outgrown voice,

sei [3] deines Schreies Natur; [4] zwar schrieest [5] du rein wie der Vogel,

be the nature of your outcry; you would indeed cry purely as a bird,

wenn ihn die Jahreszeit aufhebt, die steigende, [6] beinah vergessend,

when that time of the year, the ascending season, lifts him up, nearly forgetting

daß er ein kümmerndes Tier und nicht nur ein einzelnes Herz sei [7]

that he be a wretched animal and not only just an solitary heart,

das sie ins Heitere wirft, in die innigen Himmel. Wie er, so

which it flings into the brightness, into the inward sky. As he, so

würbest [8] du wohl, nicht minder --, daß, [9] noch unsichtbar,

would you well woo, not any less--so that, still invisible,

dich die Freundin erführ, [10] die stille [11], in der eine Antwort

your friend would sense you, she the quiet one,in whom an answer

langsam erwacht und über dem Hören [12] sich anwärmt, --

slowly awakens and warms itself up beyond hearing,

deinem erkühnten Gefühl die erglühte Gefühlin. [13]

the radiant empathizer to your emboldened feeling.

O und der Frühling begriffe [14] --, da ist keine Stelle,

Oh and the Spring would comprehend--, there is not one place

die nicht trüge [15] den Ton der Verkündigung. [16] Erst jenen kleinen

which would not carry the the tone of proclamation. At first that small

fragenden Auflaut, [17] den mit steigernder Stille [18],

questioning up-sound, which with mounting stillness,

weithin umschweigt ein reiner bejahender Tag. [19]

a pure, affirming day further surrounds with silence.

Dann die Stufen hinan, Ruf-Stufen [20] hinan zum geträumten

Then the steps upwards, summoning-steps onwards to the dreamed-of

Tempel der Zukunft --; dann den Triller, [21] Fontäne,

temple of the future--; then the trill, fountain,

die zu dem drängenden Strahl schon das Fallen zuvornimmt

which already foreshadows its thrusting stream's falling

im versprechlichen Spiel . . . [22] Und vor sich, den Sommer. [23]

with its promise-like play. And in front of itself Summer.

Nicht nur [24] die Morgen alle des Sommers [25] --, nicht nur

Not just all the mornings of sommer--, not just

wie sie sich wandeln in Tag [26] und strahlen [27] vor Anfang.

how they transform themselves into day and radiate beginningness.

Nicht nur die Tage, die zart sind um Blumen, [28] und oben,

Not just the days, which are so tender around flowers, and above,

um die gestalteten Bäume, stark und gewaltig.

around the fully-formed trees, strong and powerful.

Nicht nur [29] die Andacht dieser entfalteten Kräfte,

Not just the devotion to these unfolded powers,

nicht nur die Wege, [30] nicht nur die Wiesen im Abend, [31]

not just the paths, not just the meadows at evening,

nicht nur nach spätem Gewitter, das atmende Klarsein, [32]

not just, after a late cloudburst, the breathing clarity,

nicht nur der nahende Schlaf und ein Ahnen, abends. . . [33]

not just the nearing sleep and an intimation, evenings. . .

Sondern die Nächte! [34] Sondern die hohen, des Sommers,

But rather the nights! But rather the high ones of Summer,

Nächte, [35] sondern die Sterne, die Sterne der Erde. [36]

nights, but rather the stars, the stars of the earth.

O einst tot sein und sie wissen unendlich,

Oh to be dead some day and know them unendingly,

alle die Sterne: [37] denn wie, wie, wie sie [38] vergessen!

all of the stars: for how, how, how to forget them!

Siehe, da rief [39] ich die Liebende. Aber nicht s i e [40] nur

Look, I would call forth the loved one. But not only s h e

käme. . . [41] Es kämen aus schwächlichen Gräbern [42]

would come. . . out of feeble graves there would come

Mädchen und ständen . . . [43] Denn, wie beschränk ich,

young girls and they would stand there. . . For how can I limit,

wie [44], den gerufenen Ruf? [45] Die Versunkenen suchen

how, the called out call? Those sunken ones still are seeking

immer noch Erde. -- Ihr Kinder, [46] ein hiesig

earth -- You children, a thing from this place once

einmal ergriffenes Ding gälte, [47] für viele.

grasped is full of validity for many.

Glaubt nicht, Schicksal sei [48] mehr als das Dichte der Kindheit;

Do not believe that fate be more than the density of childhood;

wie überholtet ihr oft den Geliebten, atmend,

how often did you not overtake your loved one, breathing,

atmend nach seligem Lauf [49], auf nichts zu, ins Freie.

breathing after a blissful run, going nowhere, going into the free open spaces.

Hiersein ist herrlich. Ihr wußtet es, Mädchen, ihr auch,

Being alive is glorious. You knew it, you girls, you also

die ihr scheinbar entbehrtet, [50] versankt --, [51] ihr, in den ärgsten

who apparently did without it, sank down --, you in the most vile

Gassen der Städte, Schwärende, oder dem Abfall

alleys of the cities, you festering ones, or exposed to

offene. [52] Denn eine Stunde war jeder, [53] vielleicht nicht

filth. For to each came an hour, perhaps not

ganz eine Stunde, ein mit den Maßen der Zeit kaum

quite an hour, a period hardly measurable with the

Meßliches zwischen zwei Weilen, [54] da [55] sie ein Dasein

measures of time coming between two whiles, where she had an

hatte. Alles. [56] Die Adern voll Dasein. [57]

existence. Everything. Her veins full of being.

Nur, wir vergessen so leicht, was der lachende Nachbar

Only, we forget so easily, what the laughing neighbor

uns nicht bestätigt oder beneidet. Sichtbar

does not confirm nor envy. Visibly

wollen wirs [58] heben, wo doch das sichtbarste Glück uns

we want to elevate it, where however the most visible happiness

erst zu erkennen sich [59] gibt, wenn wir es innen verwandeln.

only lets itself be perceived, when we transform it inwardly.

Nirgends, Geliebte, wird Welt sein, als innen. Unser

Nowhere, my love, will there be world than inward. Our

Leben geht hin [60] mit Verwandlung. Und immer geringer [61]

life goes forth with transformation. And, ever diminishing,

schwindet das Außen. Wo einmal ein dauerndes Haus war,

wanes the exterior. Where once an enduring house was,

schlägt sich erdachtes Gebild [62] vor, quer, zu Erdenklichem [63]

suggests itself a mental construct, obliquely, totally belonging

völlig gehörig, als ständ es noch ganz im Gehirne. [64]

to the conceivable, as if it stood still entirely formed in the brain.

Weite Speicher der Kraft schafft sich der Zeitgeist, gestaltlos

The spirit of the times brings forth vast stockpiles of power, formless

wie der spannende Drang, den er aus allem gewinnt. [65]

as the over-arching impulsion which it wrenches from everything.

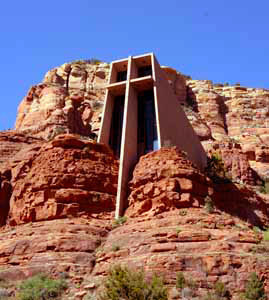

Tempel kennt er nicht mehr. Diese, des Herzens, Verschwendung [66]

It no longer knows of temples. This, the wastefulness of our heart,

sparen wir heimlicher ein. Ja, wo noch eins übersteht,

we save up ever more secretly. Yes, where yet one survives,

ein einst gebetetes Ding, ein gedientes, geknietes --, [67]

one once prayed for thing, one deserved, one knelt down for --

hält es sich, so wie es ist, schon ins Unsichtbare hin. [68]

It holds itself, just as it is, already onward into the unseeable.

Viele gewahrens [69] nicht mehr, doch ohne den Vorteil,

Many perceive it no more, without however having the advantage,

daß sie's [70] nun i n n e r l i c h [71] baun, mit Pfeilern und Statuen, größer!

that they now build it i n w a r d l y with columns and statues, yet mightier!

Jede dumpfe Umkehr der Welt hat solche Enterbte,

Every dull rotation of the world has such disinherited ones,

denen das Frühere nicht und noch nicht das Nächste gehört.

to whom what has come before does not belong and not yet what is to come. [A]

Denn auch das Nächste ist weit für die Menschen. Uns soll

For that which is to come is also distant for humans. We should not

dies nicht verwirren; es stärke [72] in uns die Bewahrung

allow us this to confuse us; it should strengthen in us the preservation

der noch erkannten Gestalt. [73] Dies [74] s t a n d [75] einmal unter Menschen,

of the still recognizable configuration. This s t o o d once among mankind,

mitten im Schicksal stands, [76] im vernichtenden, [77] mitten

it stood in the midst of fate, annihilating fate, in the midst of

im Nichtwissen-Wohin [78] stand es, [79] wie seiend, [80] und bog

not-knowing-where-to-go it stood, as if existing, and bent

Sterne zu sich aus gesicherten Himmeln. Engel,

stars to itself from the secured heavens. Angel,

dir noch zeig ich es, d a! [81] In deinem Anschaun

to you I will yet show it, t h e r e! In your gaze

steh [82] es gerettet [83] zuletzt, nun endlich aufrecht.

it stands saved at last, now finally upright,

Säulen, Pylone, der Sphinx, das strebende Stemmen,

Columns, Pylons, the Sphinx, the thrusting buttressing,

grau aus vergehender Stadt oder aus fremder, des Doms. [84]

of the cathedral, gray, from expiring or unknown cities,.

War es nicht Wunder? O staune, Engel, denn w i r sinds,

Was it not a miracle? Oh be astonished, angel, for w e are the ones,

wir, [85] o du Großer, erzähls, daß wir solches vermochten, mein Atem

we, oh you grand one, make it known, that we were able to do such things, my breath

reicht für die Rühmung nicht aus. So haben wir dennoch

is not sufficient for the praising. Thus have we

nicht die Räume versäumt, diese gewährenden, diese,

not neglected the spaces, these bestowing, these,

u n s e r e Räume. [86] (Was müssen sie fürchterlich groß sein,

o u r spaces. (How frightfully large they must be,

da sie Jahrtausende nicht unseres Fühlns überfülln. [87])

since centuries of our feelings do not overfill them.)

Aber ein Turm war groß, nicht wahr? O Engel, er war es, --

But a tower was great, was it not? Oh Angel it was that,--

groß, auch noch neben dir? Chartres war groß [88] -- und Musik

great, even next to you? Chartres was great--and music

reichte noch weiter hinan und überstieg uns. Doch selbst nur

reached yet further outward and overwhelmed us. And even only

eine Liebende, [89] o, allein am nächtlichen Fenster . . .

a loving one, oh, alone at her evening window. . .

reichte sie dir nicht ans Knie --?

did not she reach to your knee--?

Glaub n i c h t, [90] daß ich werbe.

Do not believe, that I am wooing.

Engel, und würb [91] ich dich auch! Du kommst [92] nicht. Denn mein

Angel, and even were I to woo you! You are not coming. For my

Anruf ist immer voll Hinweg; [93] wider [94] so starke

outcry is always full of distancing; against such strong

Strömung kannst du nicht schreiten. Wie ein gestreckter

streaming you cannot stride. Like an outstretched

Arm ist mein Rufen. [95] Und seine zum Greifen

arm is my crying-out. And its ready for gripping,

oben offene Hand [96] bleibt vor dir

upturned open hand remains in front of you

offen, wie Abwehr und Warnung,

open, like a warding-off and warning,

Unfaßlicher, [97] weit auf. [98]

you ungraspable one, far away up there.

[1] Werbung nicht mehr, nicht Werbung: An example of a epanodos. Epanodos The repetition of a group of words in reverse order.

[2] entwachsene Stimme: Parenthetical antecedent for both the possessive "deines" in the next clause and the subject "du" in the following one.

[3] sei: The imperative form of "sein" which is the only irregular "du-form" imperative in German.

[4] deines Schreies Natur: "die Natur deines Schreies."

[5] schrieest Konjunktiv II form of schreien. The subjunctive of this same verb, but in the first person singular "Wer, wenn ich schriee . . ." began Elegie 1 Translate as "you would cry. . . "

[6] die steigende: The feminine endings indicate that this present participle modifies "Die Jahreszeit" and not "der Vogel," which is masculine, even though the bird is also climbing. Rilke seems to be referring to spring as the ascending season. Also an epanorthosis since it further amplifies the meaning. Epanorthosis, pl. -ses: the rephrasing of an immediately preceding word or statement for the purpose of intensification, emphasis, or justification.

[7] sei: Here the Konjunktiv I form of "sein" used to indicate Indirekte Rede, since what one is forgetting is being related indirectly.

[8] würbest: Konjunktiv II of the strong verb "werben" which has an irregular Konjunktiv II form "wurben." (Imperfekt "wurb" plus umlaut and "est" ending.)

[9] daß: Read as "so daß," the repetition of "so" being indicated with the dash.

[10] erführ: Konjunktiv II of "erfahren" (Imperfekt "erfuhr" with umlaut.) Apocope since the normal form would be "erführe." Apocope: The loss of one or more sounds from the end of a word.

[11] die stille: In Apposition to "Freundin," not capitalized because it is used as modifier coming after the noun. Apposition is an explanatory noun or phrase normally placed after the noun explicated. In German it must be in the same case and set off with commas. It is also said to be in apposition to the noun or pronoun to which it refers.

[12] über dem Hören: The verb "überhören" means "not to hear" (and not "overhear"). A translation of "über dem Hören" could thus be "beyond hearing."

[13] deinem erkühnten Gefühl die erglühte Gefühlin: "The nominative "die erglühte Gefühlin" is in Apposition to the "[stille] Freundin," and "deinem erkühnten Gefühl" in the dative. This is a form of the scesis onamaton not uncommon in German. I saw an inscription on a equistrian statue in Hanover reading "Das Volk dem Kaiser." In the first case the understood verb is simply "to be": "She [is] the fired-up empathizer to your emboldened feeling." In the second instance it indicates that the statue [is given] by the people to the honor of the Kaiser. Apposition is an explanatory noun or phrase normally placed after the noun explicated. In German it must be in the same case and set off with commas. It is also said to be in apposition to the noun or pronoun to which it refers. Scesis onamaton: Omission of the only verb of a sentence.

[14] begriffe,: Konjunktiv II of "begreifen" (Imperfekt "begriff" plus "e") meaning here that "Spring would comprehend."

[15] trüge . . . Konjunktiv II of "tragen" meaning here "would not carry" or "would not wear."

[16] Ton der Verkündigung: The German word "Ton" has both of the English meanings of being a "musical tone" and the meaning of a "specific way of behaving or writing." Since this is the beginning of a series of musical metaphors, one can assume the first definition. Verkündigung can mean a very ceremonial announcement as is "Maria-Verkündigung" meaning "Annunciation" or in Wagner's "Die Walküre" where there is a "Todesverkündigung" where Sigmund has his forthcoming death announced to him by Brünnhilde. I must mention that in the trade edition which I have been using, the word "der" is missing, reading simply "Ton Verkündigung," which is just wrong. In the Thurn und Taxis Handschrift "der" is clearly present, and, of course, in the Professor Ernst Zinn edition of the Sämptlich Werke, the correction has been made. Metaphor: A figure of speech in which a word or phrase that ordinarily designates one thing is used to designate another, thus making an implicit comparison.

[17] Erst jenen kleinen fragenden Auflaut: The first of a series of metaphors in apposition to "den Ton der Verkündigung." which must all be in the accusative case. Included are "Dann die Stufen hinan" and "dann den Triller." The word "Auflaut" seems to have been invented by Rilke. "Auftakt" is an up-beat, so instead of with "an up-beat," the day begins with an "up-sound." Rilke may have wanted to continue the image with quasi-musical words which would at the same time fit in with his synesthetic imagery, in this case attributing musical properties to objects. Apposition is an explanatory noun or phrase normally placed after the noun explicated. In German it must be in the same case and set off with commas. It is also said to be in apposition to the noun or pronoun to which it refers. Metaphor: A figure of speech in which a word or phrase that ordinarily designates one thing is used to designate another, thus making an implicit comparison. Synaesthesia: A sensation produced in one modality when a stimulus is applied to another modality, as when the hearing of a certain sound induces the visualization of a certain color.

[18] den mit steigender Stille: An oxymoron, since the "Auflaut" begins with "mounting stillness." Oxymoron: A rhetorical figure in which incongruous or contradictory terms are combined, as in a deafening silence and a mournful optimist.

[19] umschweigt ein reiner bejahender Tag: Hyperbaton. The normal word order would be "den mit steigernder Stille, weithin ein reiner, bejahender Tag umschweig" The prefix "um" used with "schweigen" is unusual and in keeping with the other created words "Auflaut" and "Ruf-Stufen" which include spacial/sound imagery. The Kommienterte Ausgabe also lists "ein reiner bejahender Tag" as being an Enallage, since the adjective is misplaced: the people concerned affirm the day and not the day itself. Enallage: The use of one grammatical form in some way incorrectly in place of another, as the plural for the singular in the editorial use of "we." The basic meaning is an exchange, which can also include using an adjective with the wrong noun as in "enttäuscht wie ein Postamt am Sonntag," where the visitors and not the post office are "disappointed."

[20] Dann die Stufen hinan, Ruf-Stufen: This Epanorthosis further maintains the musical association to "Ton" with "Ruf-Stufen." The word "Stufe" besides meaning a "step" or "level" also means a "musical interval." Epanorthosis: The rephrasing of an immediately preceding word or statement for the purpose of intensification, emphasis, or justification

[21] Triller: The third of a series of musical metaphors referring back to "den Ton der Verkündigung." The accusative case of "den Triller" shows it to be in Apposition to the accusative "den Ton der Verkündigung." Apposition is an explanatory noun or phrase normally placed after the noun explicated. In German it must be in the same case and set off with commas. It is also said to be in apposition to the noun or pronoun to which it refers. Metaphor: A figure of speech in which a word or phrase that ordinarily designates one thing is used to designate another, thus making an implicit comparison.

[22] Fontäne, die zu dem drängenden Strahl schon das Fallen zuvornimmt im versprechlichen Spiel: An extended image in apposition to the appositiv "Triller," while at the same time being an extremely complicated synesthetic metaphor. The preceeding word "Triller" is a continuation of the musical metaphors. A trill in nineteenth-century music begins on the tone to be trilled and then alternates between it and the next diatonic tone above it. A fountain rises up and then falls back. Rilke sees the rising of the stream of water as a foreshadowing of its falling in the same way that the beginning of the trill and each of its alternate notes foreshadows the final descent to the note itself, i.e. to its starting point; therefore, both the musical note and the rising of the jets of water are "promise-like." (The word "versprechlich" seems to be a neologism with the meaning of promise-like.) Were we to envision a pulsating fountain like the one in front of the "Bellagio Hotel" in Las Vegas, the metaphor would be apt. Apposition is an explanatory noun or phrase normally placed after the noun explicated. In German it must be in the same case and set off with commas. It is also said to be in apposition to the noun or pronoun to which it refers. Metaphor: A figure of speech in which a word or phrase that ordinarily designates one thing is used to designate another, thus making an implicit comparison.

[23] den Sommer: The last and almost symphonic climax to the string of musical images in Apposition to "den Ton der Verkündigung." Climax: A series of statements or ideas in an ascending order of rhetorical force or intensity. Apposition is an explanatory noun or phrase normally placed after the noun explicated. In German it must be in the same case and set off with commas. It is also said to be in apposition to the noun or pronoun to which it refers.

[24] Nicht nur: An anaphora with a series of eight repetitions of "nicht nur" as the first part of an extended antithesis. Anaphora: The deliberate repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of several successive verses, clauses, or paragraphs. Anaphora: The deliberate repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of several successive verses, clauses, or paragraphs. Antithesis: A figure of speech in which sharply contrasting ideas are juxtaposed in a balanced or parallel phrase or grammatical structure.

[25] die Morgen alle des Sommers: An anastrophe since normal order would be "alle die Morgen des Sommers." Anastrophe: Inversion of the normal syntactic order of words; for example, "Matter too soft a lasting mark to bear."

[26] nicht nur wie sie sich wandeln in Tag: Hyperbaton. Normal word order would be "wie sie sich in Tag wandeln . . ." Continuation of the anaphora with the second repetition of "nicht nur." Anaphora: The deliberate repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of several successive verses, clauses, or paragraphs.

[27] strahlen: Hyperbaton. Normal word order would be "und vor Anfang strahlen. . ." Hyperbaton: A figure of speech, such as anastrophe or hysteron proteron, using deviation from normal or logical word order to produce an effect.

[28] Nicht nur die Tage, die zart sind mit Blumen: Continuation of the anaphora with the third repetition of "nicht nur." Hyperbaton. Normal word order would be "die zart um Blumen sind" Anaphora: The deliberate repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of several successive verses, clauses, or paragraphs.

[29] Nicht nur: Continuation of the anaphora with the fourth repetition of "nicht nur." Anaphora: The deliberate repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of several successive verses, clauses, or paragraphs.

[30] Nicht nur die Wege : Continuation of the anaphora with the fifth repetition of "nicht nur." Notice the shortening of the phrase to "nicht nur die Wege" similar to "stretto" in music. Anaphora: The deliberate repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of several successive verses, clauses, or paragraphs.

[31] Nicht nur die Wiesen im Abend: Continuation of the anaphora with the sixth repetition of "nicht nur." Also a shortened phrase with "nicht nur die Wiesen in Abend," along with two long vowels--"ie" and "A." Anaphora: The deliberate repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of several successive verses, clauses, or paragraphs.

[32] Nicht nur, nach spätem Gewitter, das atmende Klarsein: Continuation of the anaphora with the seventh repetition of "nicht nur." Approaching the end of the anaphora, the tempo slows down with a longer phrase with two long "a" vowels in "das atmende Klarsein." Anaphora: The deliberate repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of several successive verses, clauses, or paragraphs.

[33] nicht nur der nahende Schlaf und ein Ahnen, abends: Conclusion of the anaphora with the eighth repetition of "nicht nur." A definite deaccelendro concluding with four long "a" sounds, "nahende Schlaf und ein Ahnen, abends" creating a prolonged assonance with the last two words,"Ahnen" and "abends," beginning with long "a." Anaphora: The deliberate repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of several successive verses, clauses, or paragraphs. Assonance: The repetition of identical or similar vowel sounds, especially in stressed syllables.

[34] Sondern die Nächte: An anaphora. This time with a series of three repetitions of "sondern die" which concludes the antithesis begun with the eightfold use of "nicht nur." Nestled within the anaphora is also an inclusio with the word "Nächte" surrounding the phrase "Sondern die hohen, des Sommers." Anaphora: The deliberate repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of several successive verses, clauses, or paragraphs. Inclusio: An epanalepsis used to mark off a whole passage.

[35] Sondern die hohen, des Sommers, Nächte: Instead of "die hohen Nächte des Sommers" Rilke has put the possessive "des Sommers" before "Nächte," ending up with an Anastrophe. Also the second repetition of "Sondern die" continuing the anaphora. Anaphora: The deliberate repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of several successive verses, clauses, or paragraphs. Anastrophe: Inversion of the normal syntactic order of words.

[36] sondern die Sterne, die Sterne der Erde: An Epanorthosis, since the repetition further explicates. The third and last repetition of "sondern die" concluding the antethisis with the last anaphora. Also used as an anticipatory direct object of "wissen" in the next sentence. Epanorthosis: The rephrasing of an immediately preceding word or statement for the purpose of intensification, emphasis, or justification. Anaphora: The deliberate repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of several successive verses, clauses, or paragraphs. Antithesis: A figure of speech in which sharply contrasting ideas are juxtaposed in a balanced or parallel phrase or grammatical structure.

[37] alle die Sterne: A further Epanorthosis referring back to "die Sterne der Erde." Epanorthosis: The rephrasing of an immediately preceding word or statement for the purpose of intensification, emphasis, or justification.

[38] wie, wie, wie sie: An epizeuxis with the simple threefold repetition plus a Binnenreim with "sie." Epizeuxis: Repetition with no words intervening. Binnenreim: Reim innerhalb der Verszeile.

[39] rief . . . Since Rilke often omits the "e," an apocope, from the subjunctive II verb forms, this could be a shortened form of "riefe" (to avoid three unaccented syllables) which would be consistent with the following series of irreal results of this calling, expressed with the clear Konjunktiv II verbs "käme, kämen and ständen." It would then be translated as "Look, there I would call the loved one." Apocope: The loss of one or more sounds from the end of a word.

[40] s i e: First instance of Sperrdruck in this Elegie. Comes on unaccented syllable. Sperrdruck: Spaced type formerly used for Italics and found in the Elegien. In modern editions replaced with italics.

[41] käme: Konjunktiv II of "kommen."

[42] Es kämen aus schwächlichen Gräbern: According to the Kommentierte Ausgabe another example of Enallage in this Elegie. "Die Gräber" are not "schwächlich," but rather the resurrected inhabitants. Also an anticipatory "es" to emphasize the verb which is the Konjunktiv II of kommen. The use of one grammatical form in some way incorrectly in place of another, as the plural for the singular in the editorial use of "we." The basic meaning is an exchange, which can also include using an adjective with the wrong noun as in "enttäuscht wie ein Postamt am Sonntag," where the visitors and not the post office are "disappointed."

[43] ständen: Konjunktiv II of "stehen."

[44] wie beschränk ich, wie: A Diacope. The missing "e" on "beschränk" is an apocope. Notice here how Rilke uses the indicative of "beschränken," putting the question to the reader. Diacope: Repetition with only a word or two between. Apocope: The loss of one or more sounds from the end of a word.

[45] den gerufenen Ruf: A polyptoton with the use of the past participle of the verb "rufen" as an adjective modifying the noun formed from the same root. Polyptoton: The repetition of the same word or root in different grammatical functions or forms.

[46] Ihr Kinder: An Apostrophe to the young persons who are now addressed in the following sentences. Apostrophe: The direct address of an absent or imaginary person or of a personified abstraction, especially as a digression in the course of a speech or composition.

[47] gälte: Konjunktiv II form of gelten.

[48] sei: Konjunktiv I of sein used because of indirekte Rede. Rilke is reporting what they are not to believe.

[49] atmend, atmend nach seligem Lauf: An anadiplosis, beginning a phrase with the last word of the preceding one. Anadiplosis: : Rhetorical repetition at the beginning of a phrase of the word or words with which the previous phrase ended.

[50] entbehrtet: The elliptical direct object is "es" and is not repeated, since it has been stated in the preceding clause. Ellipsis: The omission of a word or phrase necessary for a complete syntactical construction but not necessary for understanding.

[51] versankt: Since both "entbehrtet" and "versankt" are used together, we see another reason for not repeating the "es," since only "entbehrtet" would apply. The dash after "versankt" and the repetition of "ihr" indicates that the following does not relate back to these verbs, but is free-standing. Note also the "asyndeton," since normally you would find "entbehrtet und versankt."

[52] ihr, in den ärgsten Gassen der Städte, Schwärende, oder dem Abfall offene: A scesis onamaton, since there is no verb and the dash in the preceeding phrase precluded the use of that phrase's verb. The "ihr" which begins the phrase is its fourth repetition, three times at the beginning of a phrase, which is a anaphora and once after "die." This anaphora is to prepare us for this extended apostrophe, which by its nature needs no verb. The phrase itself presents some difficulty in comprehension. In the earlier editions there is a discrepency in that "Schwärende" is capitalized while "offene" in a seemingly parallel phrase is not. "Schwärende" means something like " festering girls" in apposition to "ihr," since "you festering ones" would be ihr Schwärenden; The later editions have capitalized "Offene." In Rilke's handwritten copy which he sent to Fürstin Marie von Thurn und Taxis-Hohenlohe, to whom he dedicated the "Elegien," printed in a facsimile edition in 1947/48, it is clear that "Offene" should be capitalized. I have not seen the type-script, so cannot confirm that it may yet be there. With this change it is now possible to translate the two phrases as parallel "You, in the most vile streets of the city, festering ones, or exposed to filth." Anaphora: The deliberate repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of several successive verses, clauses, or paragraphs. Apostrophe: The direct address of an absent or imaginary person or of a personified abstraction.

[53] jeder: A dative feminine form meaning something like "for each of you there was an hour . . . "

[54] vielleicht nicht ganz eine Stunde, ein mit den Maßen der Zeit kaum Meßliches zwischen zwei Weilen: An entended epanorthosis. Note also the polyptoton with "Maßen" and "Meßliches," coming from the verb "messen, maß, gemessen." Epanorthosis: The rephrasing of an immediately preceding word or statement for the purpose of intensification, emphasis, or justification. Polyptoton: The repetition of the same word or root in different grammatical functions or forms.

[55] da: The conjunction "da" may be used in place of "wo" according to Duden: "da/wo: Beide Relativadverbien müssen sich auf ein Substantiv (oder Adverb) beziehen, das entweder Ort oder Zeit bezeichnet: 'Kein Tag vergeht, da du nicht weinst' (Frisch, Cruz 58)."

[56] Alles: In apposition to the direct object of the previous phrase "da sie ein Dasein hatte." Read as "da sie alles hatte." Also a scesis onamaton, having no verb. Apposition is an explanatory noun or phrase normally placed after the noun explicated. In German it must be in the same case and set off with commas. It is also said to be in apposition to the noun or pronoun to which it refers. Scesis onamaton: Omission of the only verb of a sentence.

[57] Die Adern voll Dasein: A scesis onamaton describing the existence which is everything. Note also the apocope of "voll Dasein," normally "voller Dasein." In the previous Elegie, the same issue of translating "Adern" as "veins" arose. To repeat: "German uses "Adern" which means 'artery' to indicate a 'Wesenszug' or essential characteristic, while English uses 'veins' to indicate 'a pervading character or quality; streak.' Therefore to convey the meaning, one has to literally mistranslate the word."

[58] s: A direct object neuter pronoun referring back to its antecedent "Dasein." Also note the Synaloepha. Synaloepha: Omission of a vowel to contract two words into one such as "don't," "it's."

[59] sich: Hyperbaton: Normal word order would be "wo doch das sichtbarste Glück sich uns erst zu erkennen gibt . . ."

[60] hin: Hyperbaton. Normal word order would be "Unser Leben geht mit Verwandlung hin."

[61] immer geringer: "Immer geringer" modifies the subject, since the verb "schwinden" already means "to diminish" or "wane," with the understanding that "immer geringer" stands for "das immer geringer wird." The whole sentence would then read "Und das Außen, das immer geringer wird, schwindet." The difference between "schwinden" and "verschwinden" is that the latter means "to disappear."

[62] erdachtes Gebild: "Erdacht" is an adjective formed from the past participle of the verb "erdenken" which means to invent or according to Sprach-Brockhaus "schaffe im Geist." "Gebild" is something "formed" or "constructed." According to Brockhaus "Gestaltetes, Geformtes, Erzeugnis." English "mental construct" is probably the closest translation.

[63] zu Erdenklichem: Polyptoton, since the abstract noun comes from the verb "erdenken, erdacht, erdenken," which is the same stem as for the word "erdachtes" in the image "erdachtes Gebild." Also a Nominalisierung. "Erdenklich" means "alles nur mögliche, soviel sich nur denken lässt." Brockhaus. Polyptoton: The repetition of the same word or root in different grammatical functions or forms. Nomanilisierung: The creation of an abstract noun from any part of speech. In German, all that is needed is to capitalize the word, be it verb, adverb, pronoun, past or present participle or conjunjction, and add the requisite case endings, if any. All such constructions are in the neuter gender.

[64] als ständ es noch ganz im Gehirne: Shortened form of "als ob es noch ganz im Gehirne ständ." Note the apocope of "ständ."

[65] gewinnt: According to Sprach-Brockhaus one of the meanings of "gewinnen" is "bringe in meinen Besitz." An English translation would be "to appropriate from" or more dramatically "to wrench from."

[66] Diese, des Herzens, Verschwendung: "Diese Verschwendung des Herzens."

[67] gedientes, geknietes: Asyndeton. Normal would be "gedientes und geknietes." Note how these two past participial adjectives are continuing modifiers of the word "Ding," but placed after it for emphasis using the asyndeton. Also serving as an Epanorthosis, because it further explicates "Ding." Epanorthosis: the rephrasing of an immediately preceding word or statement for the purpose of intensification, emphasis, or justification,

[68] hält es sich, so wie es ist, schon ins Unsichtbare hin . . .There is sort of a verbal oxymoron, since the first two verbs "sich halten" and "sein" indicate position and stability, while the verbless "schon ins Unsichtbare hin" indicates motion into the invisible. A translation would be "It holds itself, just as it is, already ownward into the unseeable."

[69] gewahrens: Not to be confused with gewähren which means to grant. The verb gewahren means "to perceive." Note the synaloepha without an apostrophe of "gewahr es." Synaloepha: Omission of a vowel to contract two words into one such as "don't," "it's."

[70] sie's: Since in the preceeding main clause there is a synaloepha without an apostrophe with "gewahrs," why is there an apostrophe in "sie's?" Rilke uses a synaloepha without an apostrophe with most other pronouns, such as "ihrs," "wirs" and "ers;" there are, however, no "dus" or "sies." Synaloepha: Omission of a vowel to contract two words into one such as "don't," "it's."

[71] i n n e r l i c h: Second Sperrdruck if this Elegie. Hier placed on an accented word to further streess one of the main themes of the Elegien. Sperrdruck: Spaced type formerly used for Italics and found in the Elegien. In modern editions replaced with italics.

[72] es stärke; Konjunktiv I form of "stärken" used as a third person command. In German this is called a "Wunsch und Begehrungssatz" and exists mainly in Biblical and poetic expressions such as "Der Herr segne dich und behüte dich!," "Es lebe hoch!," "Es lebe die Freiheit!," "Es werde Licht," etc. An English translation would be "let it strengthen in us . . . " Formed from Konjunktiv I. Wunsch und Begehrungssatz: A use of Konjunktiv I to express a wish or desire, normally in the third person as commands.

[73] die Bewahrung der noch erkannten Gestalt: An extrordinarily difficult to translate phrase, since it represents the ideal which we have preserved from our past which is worthy of the angels. Normally translated as something like the "still recognized form," which comes across as unworthy of all the praise Rilke further devotes to it. The most untranslatable word is "Gestalt" which in German represents a wholeness, the parts of which cannot be separated. The American Heritage Dictionary gives as its second definition of "configuration": "Psychol. A gestalt." The meaning of "erkannt" as "recognizable" fits the context.

[74] Dies: Coming right after die "Bewahrung der noch erkannten Gestalt" one would expect that the "This" would refer to the Gestalt, "the form." Were this so the feminine form "Diese" would be required. Not only "dies," but also "stands" which is a synaloepha of "stand es" and the further "stand es" mean that the antecedent is a concept, not an individual word, which makies it neuter. The antecedent is therefore the "Bewahrung der noch erkannten Gestalt."

[75] s t a n d: Third example of Sperrdruck emphasizing the importance of the existence of "die Bewahrung der noch erkannten Gestalt" among humankind. First of three repetitions of "stand" or "stands." The first two repetitions are an Epanalepsis. The two repetitions before and after "im vernichtenden, mitten im Nichtwissen-Wohin" constitute an inclusio. Epanalepsis A repetition of a word or phrase with intervening words setting off the repetition, sometimes occuring with a phrase used both at the beginning and end of a sentence. Inclusio: An epanalepsis used to mark off a whole passage. Sperrdruck: Spaced type formerly used for Italics and found in the Elegien. In modern editions replaced with italics.

[76] stand es: second repetition of "stand" with a Synaloepha on "s." Synaloepha: Omission of a vowel to contract two words into one such as "don't," "it's.

[77] im vernichtenden: An anastrophe, since the word "Schicksal" has its modifier placed afterwards and also after the same dative contraction "im." Anastrophe: Inversion of the normal syntactic order of words. Anastrophe: Inversion of the normal syntactic order of words.

[78] Nichtwissen-Wohin: Nominalisierung using a hyphen. Nominalisierung: The creation of an abstract noun from any part of speech. In German, all that is needed is to capitalize the word, be it verb, adverb, pronoun, past or present participle or conjunjction, and add the requisite case endings, if any. All such constructions are in the neuter gender.

[79] stand: Third repetition of "stand" concluding the Inclusio. inclusio: An epanalepsis used to mark off a whole passage.

[80] wie seiend: Past Participle of verb "sein." After the threefold usage of the past form "stand," the statement "as if existing" makes clear that this "Bewahrung der noch erkannten Gestalt" is no longer prevalent, and it will be up to us to reinstate it. Note the continuation of the past tense for our previous ability to realize this ideal.

[81] d aFourth example of Sperrdruck emphasizes the place where the angels can see and help carry out the act of preservation. Sperrdruck: Spaced type formerly used for Italics and found in the Elegien. In modern editions replaced with italics.

[82] steh: Another "Wunsch und Begehrungssatz." Translate as "Let it stand redeemed . . . " "steh" is an apocope, since the full form is "stehe." Apocope: The loss of one or more sounds from the end of a word. Wunsch und Begehrungssatz: A use of Konjunktiv I to express a wish or desire, normally in the third person as commands.

[83] gerettet: Hyperbaton. Normal word order would be Steh es zuletzt gerettet . . .

[84] das strebende Stemmen, grau aus vergehender Stadt oder aus fremder, des Doms: Another example of a split possessive. The normal form would be "das strebende Stemmen des Doms, grau aus vergehender Stadt oder aus fremder." To add to the complexity "grau" is an anastrophe, since it normally would come before Stemmen as "das graue, strebende Stemmen." One would also normally write "aus vergehender oder aus fremder Stadt." The whole phrase in normal prose would be "das graue, strebende Stemmen des Doms aus vergehender oder fremder Stadt." Anastrophe: Inversion of the normal syntactic order of words.

[85] w i r sinds, wir: Fifth example of Sperrdruck emphasizing that we humans were capable of creating something worthy of the angels. A further emphasis comes with the Diacope with the repetition of "wir." Diacope: Repetition with only a word or two between. Sperrdruck: Spaced type formerly used for Italics and found in the Elegien. In modern editions replaced with italics.

[86] diese gewährenden, diese, u n s e r e Räume: Fourth example of Sperrdruck to further stress our contributions. The grammatical question is why the weak ending "en" on "gewährenden" and the strong ending "e" on "unsere." The answer is that "gewährenden" is an adjective and must take the weak ending. The possessive adjective "unsere" is itself a main modifying word and is not affected by any preceeding modifiers. According to Duden: "dieser + Possessivpronomen : Nicht: Mit diesem seinen ersten Blick hatte er viel Erfolg." Sondern "Mit diesem seinem ersten Blick hatte er viel Erfolg." Auch nach "dieser" wird das Possessivpronomen stets stark gebeugt." I am only mentioning this, because in the later editions edited by Ernst Zinn this mistake is present: "diese gewährenden, diese unseren Räume." In the "Thurn und Taxis Handschrift" there is no comma between "diese" and "u n s e r e," but the ending is definitely an "e." Also an Epanorthosis, since this phrase refers back to the previous phrase "So haben wir dennoch nicht die Räume versäumt." Sperrdruck: Spaced type formerly used for Italics and found in the Elegien. In modern editions replaced with italics. Epanorthosis: The rephrasing of an immediately preceding word or statement for the purpose of intensification, emphasis, or justification.

[87] Jahrtausende nicht unseres Fühlns überfülln: Another example of an element interposed into the middle of a possessive. Normal word order would be "Jahrtausende unsers Fühlns nicht überfülln." Note the syncope in Fühlns and in überfülln. Also note the deliberate assonance between "Fühlns" and "überfülln." Syncope: The shortening of a word by omission of a sound, letter, or syllable from the middle of the word.Assonance: Resemblance of sound, especially of the vowel sounds in words.

[88] Aber ein Turm war groß, nicht wahr? O Engel, er war es,--groß, auch noch neben dir? Chartres war groß: the threefold repetition of "groß" at the end of three phrases is an epistrophe. Note the question mark after what appears to be a statment "O Engel, er war es,--groß, auch noch neben dir?" After the first "groß" there was also a question mark after "nicht wahr." Here there is no "nicht wahr," but a lingering question mark. After the third repetition with "Chartre war groß--und Musik reichte noch weiter hinan und überstieg uns," the question mark is gone and a level of certainty has been attained. Epistrophe: The repetition of a word or words at the end of two or more successive verses, clauses, or sentences.

[89] eine Liebende:This and the phrase following it serve as an anticipatory subject for the "sie" in the question "reichte sie dir nicht ans Knie--?

[90] Glaub n i c h t: Last Sperrdruck in this Elegie adding extra force to the end of groveling to the angel. Note the apocope on "Glaub" to make the "n i c h t" more emphatic. Sperrdruck: Spaced type formerly used for Italics and found in the Elegien. In modern editions replaced with italics. Apocope: The loss of one or more sounds from the end of a word.

[91] würb: Konjunktiv II of the verb "werben" with an apocope becaus of the meter. The subordinate conjunction "wenn" has also been left off. The normal order would be "Auch wenn ich würb." Apocope: The loss of one or more sounds from the end of a word.

[92] kommst: Note that Rilke does not use the normal Konjunktiv II resolution form "Du kämest nicht" but rather switches to the indicative indicating the reality of the non-coming.

[93] voll Hinweg: Apocope for "voller Hinweg." The "Kommentierte Ausgabe" points out that the word "Hinweg" can be read as "Hinweg" which means "Weg zum Ziel" and "hinweg" which means "fort" and "weg von hier." I tried to encompass both meanings with the word "distancing."

[94] wider: Archaic, poetic form of "gegen." Still present in words like "Widerspruch." In the "Thurn und Taxis Handschrift" the normal preposition "gegen" is used. Perhaps "wider" was preferred, because of its more Biblical associations.

[95] Wie ein gestreckter Arm ist mein Rufen: Another synaesthetic simile comparing a spoken command to a physical gesture, this time a simile with the use of "wie." Synaesthesia: A sensation produced in one modality when a stimulus is applied to another modality, as when the hearing of a certain sound induces the visualization of a certain color.

[96] seine zum Greifen oben offene Hand: An extended modifier. Unextended would be "seine offene Hand, die oben zum Greifen ist." Continuation of the synaesthetic image, in that the "Rufen" now has a hand. Synaesthesia: A sensation produced in one modality when a stimulus is applied to another modality, as when the hearing of a certain sound induces the visualization of a certain color.

[97] Unfaßlicher: Refers back to der "Engel" which in German is a masculine word. There is a word play which further explains why the hand continues to remain open, signified with the repetition of the word "offen." "Unfaßlicher" in this context has both its normal meaning of "incomprehensible one" or "inconceivable one" but also retains the root meaning of the verb "fassen" which is "to seize" or "to grasp", i.e. one can neither comprehend nor physically seize an angel. The closest word in English is probably "ungraspable one."

[98] weit auf: The later editions have this as one word "weitauf." The word "weitab" means "far away" or "a long way from here." Analogous thereto "weit auf" could mean "far up there" further emphasizing the distance between man and the angel. In the "Thurn und Taxis Handschrift" it appears to be one word.

[A] Every dull rotation of the world has such disinherited ones, to whom what has come before does not belong and not yet what is nearest to them.: Erich Heller in his series of essays entitled The Disinherited Mind, uses these lines as a prefatory quote. His translation reads: "Each torpid turn of the world has such disinherited children, to whom no longer what's been, and not yet what's coming belongs."